Compliance

ESG, Where Are We Now?

A look at how ESG is taking hold in different markets, where regulation is coming down on fund managers to deliver what is on the tin, and other issues at work in this advancing sector.

The US is now the fastest growing market for ESG, giving heart to the wealth industry as ESG funds are overwhelmingly actively managed. Research recently published by global consultancy Deloitte shows that Europe still leads the sector with ESG funds totaling $14.1 trillion but suggests that the US is catching up fast.

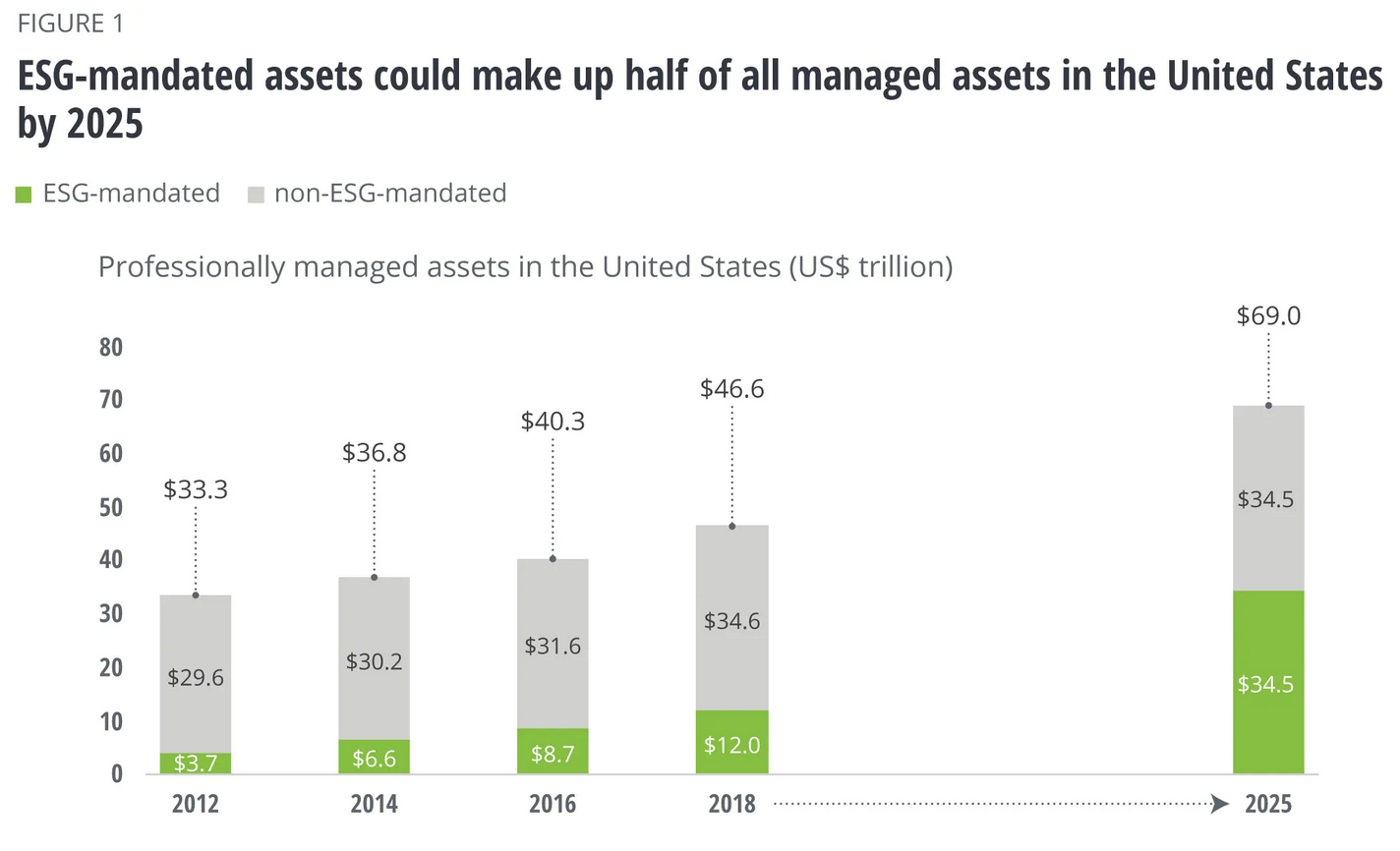

Between 2014 and 2018, assets under management in the US with an ESG mandate, among retail and institutional investors, grew by 16 per cent, compared with just 6 per cent in Europe. Flows into sustainable funds in the US reached $8.9 billion in the first six months of 2019, compared with $5.5 billion for the whole of 2018. Whether those funds meet the test of more hardened values-based investors is a different matter.

Nevertheless, the consultancy reckons that half the US market will be measured under some form of ESG criteria in the next five years, boosting growth to $34.5 trillion by 2025 from $12 trillion today. It cited demand from retail and institutional investors as the top reason managers gave for incorporating ESG into their portfolios.

The good news amid a flurry of growth and interest in sustainable investing is that the majority of ESG funds (92 per cent by Deloitte's measure) are delivered through actively managed portfolios. What is less clear as the market matures is how expensive allocation into ESG funds will become as regulators and investors demand more transparency and better reporting on the impact they are delivering. Deloitte expects around 200 new "ESG" labeled products in the US market this year.

Regulators are tooling up

Seen as a giant now stirring, the US in Congress has proposed

requiring companies to include ESG metrics as part of their

annual SEC disclosures. Companies want more harmonisation and

have petitioned the SEC to help clarify the market. Similarly, US

pensions funds are under fire to safeguard investors as part of

the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. Compliance requires

the country's mammoth pension holdings to show that ESG investing

benefits the long-term growth of these plans.

Oh for some harmonization

The EU has been pushing perhaps the longest and hardest for a

reliable ESG roadmap, including more credible and uniform

reporting and clear product labeling. The bloc has taken a tough

stance, including releasing a new taxonomy and carbon targets

this month under its contentious new “green deal” to get climate

action moving.

The Institute for International Finance (IIF) has warned how fragmented and unreliable green finance has become. The organization representing the global finance sector acknowledged "increasing coordination" among standards setters, of which there are many, but said that "regulatory and policy fragmentation” is rapidly becoming a reality at the country level. A survey of its members found that two-thirds were deeply concerned about the current regulatory quagmire, and the institute suggested that it was up to the G20 to sort it out. The opportunity may arise for those heading to the next COP outing in Glasgow later this year.

The European Securities and Markets Authority is another stepping up pressure adding a raft of duty of care rules on how financial advisors are integrating ESG. Advisors must now explain why sustainability factors are not being considered as part of their investment process, and “might explain why 97 per cent of institutional investors in Europe are interested in ESG," Deloitte said. Also why ESG enquiries from investors can’t be brushed off lightly by wealth planners.

Asia’s course

In a region where much of the new wealth is being created,

regulators have been using stronger ESG disclosures to attract

foreign capital. In 2018, in a bid to increase transparency and

investment, the Chinese government made it compulsory for listed

companies and bond issuers to disclose their ESG-related risk.

Similarly as an early booster of ESG in the region, Singapore has seen its capital markets develop faster as a result of a decision in 2016 to mandate sustainability reporting, in the hopes of giving investors more confidence in the quality of ESG data.

If there is a unifying theme in the current ESG narrative, it is around data. In what has been billed as a vast realignment of assets to put economies on more sustainable footings, fund managers admit that the biggest barrier to ESG speeding up this transition is a lack of consistent data across asset classes.

Also curtailing progress is the fact that ESG disclosures are monopolized by a handful of large-cap companies that can too easily skew performance benchmarks, and has stirred debate about where big energy companies fit.

The Wall Street Journal recently called out the ESG conundrum noting that around “eight of the 10 biggest US sustainable funds are invested in oil and gas companies,” the same ones regularly slammed by environmental activists. Environmental funds run by large asset managers aren't going to eschew fossil fuels while they are helping them beat the broader market. BlackRock is an example. Abandoning fossil fuel companies also doesn’t help an orderly low carbon transition, but it does complicate navigating ESG for investors and avoiding greenwashing.

Another challenge is reliant on the industry using more forward-looking rather than historical data to match ESG principles to impact performance. Carbon emissions are one example of where reporting is nowhere near consistent across companies or industries for providing reliable data to feed into performance. The landscape is littered with uneven disclosures.

Most managers agree that they could improve their overall offerings to investors if they could provide ESG performance impact on top of financial performance. That said, Deloitte found that less than half currently even share ESG data with their institutional clients and less than a third do so with retail clients, suggesting that there is a gap between sentiment and reality.

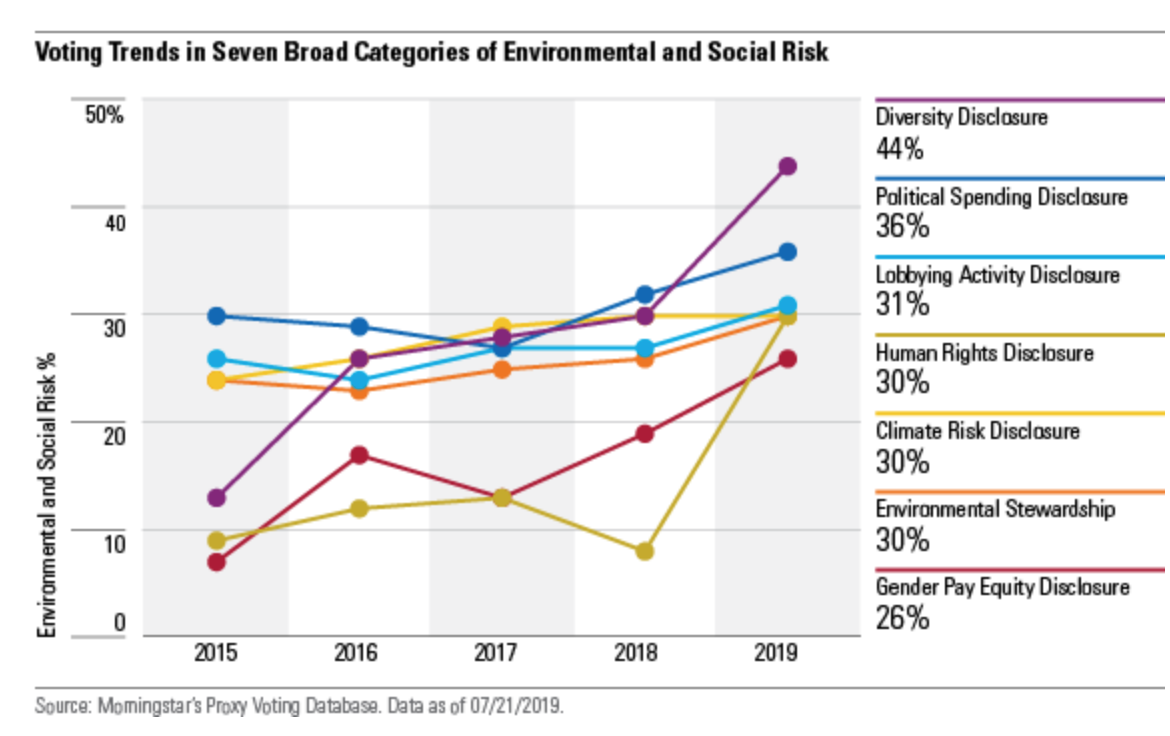

There is evidence that the information gap is closing. A recent Financial Times survey of some of the world's leading asset managers found that the number of people firms are hiring into stewardship roles almost doubled between 2017 and 2020. While not at the sharp end of analytics, these roles help drive board discussions on environmental disclosures and have a bearing on voting at annual meetings. The FT's research of around 30 large asset houses found that BlackRock’s stewardship team had risen most by around 80 per cent over the past three years, with Vanguard up by 75 per cent in second; and State Street Global Advisors third. Those recruiting in the space see demands from large pensions funds predominantly driving trends.

Measuring externalities

Developing better analytics among the larger institutions has

been evident in more M&A activity as big firms snap up stakes

in leading data and risk providers.

Within that space, more tools are being developed to track company activity, which really is where the ESG journey begins. AI engines are being used to scan more unstructured data for ESG risk, whether a company has chosen to report such risk or not. Running AI searches on patent filings, for example, to spot companies closing in on new low-carbon technologies is one way firms can get a jump on advanced screening techniques. MSCI estimates that only 35 per cent of the data used to compile company ESG ratings comes from voluntary company disclosures. Satellite data is another in wider use to help risk assessment, especially in extraction industries most under threat. Applying technology to vet companies and investments in some ways knows no bound. The two-hander will be marrying the tools with strong reporting regulations.

Where money managers see the next growth phase in ESG is in product customization, according to Deloitte; progress here should help investors separate basic ESG from more impact driven allocations, although these are very much early days.