In spite of domestic resistence to an Olympics already delayed by a year, Japan has accomplished the first stage of hosting the games, even as analysts expect the muted nature of the event to reap little of the economic benefits previous host nations have enjoyed. With the Paralympics still to come, the insular nation remains on the world's TV screens this month. Here senior Asia economist Carlos Casanova examines Japan's economic outlook for the rest of 2021 and how playing host to these unusual games has highlighted structural shortcomings.

The Olympic flame burns weak, much like Japan’s consumer sentiment

The 1992 Barcelona Olympics were a barometer of their time. They took place in the aftermath of the collapse of the Berlin Wall, in a world that was seeking to integrate, not decouple. For the first time since 1972, no countries boycotted the event.

Paralympic archer Antonio Rebollo ignited the Olympic cauldron by shooting a flaming arrow over it, while soprano Montserrat Caballé performed the emblematic soundtrack for the games in an emotive tribute to Freddie Mercury. In contrast, the Tokyo Olympics have been marred by hurdles from the onset – not only taking place during a global pandemic, they also highlight Japan’s structural shortcomings.

Inevitably, the image of Rebollo’s humble arrow springs to mind. When former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe came into power in 2012, he introduced an ambitious set of policies that aimed to shake Japan’s economy out of a long period of secular stagnation and deflation. “Abenomics” encompassed three “arrows”: 1) printing additional currency to support exports and stoke inflation; 2) increasing fiscal spending to stimulate private consumption; and 3) implementing structural reforms to boost labour productivity. But, as the resignation of the Tokyo Olympics Chief over sexist remarks earlier this year has highlighted, a lot of work is still required on the “missing arrow” front.

Despite these hurdles, the Tokyo Olympics began on 23 July even as Tokyo announced its fourth state of emergency, adding to social distancing measures that have impacted 10 prefectures covering 50 per cent of GDP since April. As a result, no international spectators were allowed. Additionally, in June, Emperor Naruhito expressed “concerns” that the Olympics might cause a rise in infections.

The rebuke was surprising as the topic remains divisive, with 68 per cent of respondents surveyed by Asahi Shimbun in July stating that they didn’t believe the Olympics could be held safely.

Against this backdrop, UBP expects that the Olympics will only deliver a marginal boost to the economy. The silver lining is that vaccination rates picked up ahead of the Games. According to figures compiled by the Johns Hopkins University, 23 per cent of Japan’s population had been fully vaccinated up to July.

Nevertheless, vaccination rates remain lower than those in other developed markets such as the UK (54 per cent), Spain (52 per cent), US and Singapore (49 per cent), and Germany (47 per cent).

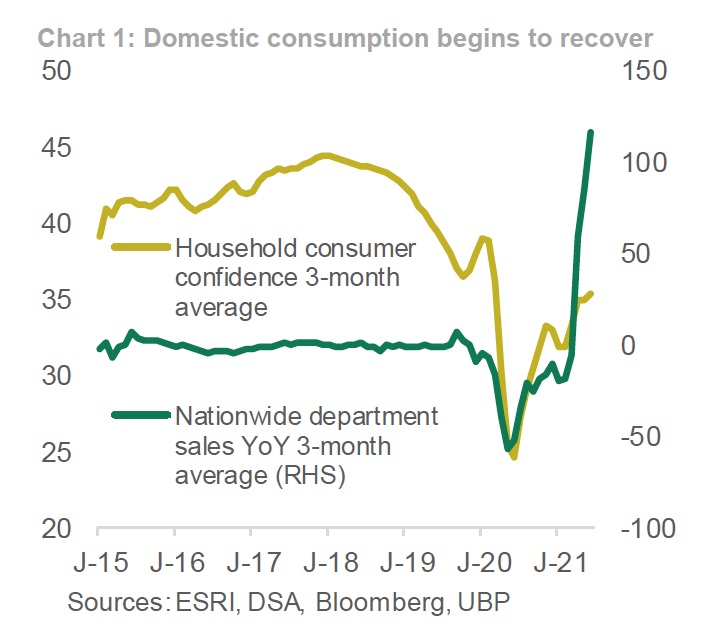

This should provide some tailwind behind domestic consumption in H2. But much like the Olympic flame, Japanese consumer sentiment remains weak. Household consumer confidence improved from its 2020 trough in June but remained significantly below pre-COVID levels (Chart 1). The latest SOE is likely to dampen consumer sentiment further, delaying the recovery in domestic consumption.

Before the latest coronavirus wave, department sales nationwide increased to 37.4 per cent year-on-year to June. Admittedly, these were supported by a strong favourable base effect, something that will continue for the remainder of 2021, but it also points to a latent propensity to consume following months of SOE. As a result, we project that domestic consumption will recover, albeit gradually, in the remainder of 2021.

On the flip side, manufacturing activity, which has acted as a key driver of growth in H1-21, is expected to decline. The latter has remained supported by better demand from Japan’s largest export markets: US (20 per cent of total) and China (19 per cent).

As a result, exports increased 49.6 per cent year-on-year to May, or 21.1 per cent year-on-year on average in the first five months of this year. However, both economies have shown signs of peaking and will enter a more mature stage of recovery in H2-21 – arguably already underway for China.

US inventories increased 4.5 per cent to June and are back to pre-COVID levels, which is likely to translate into slower demand for Japanese exports in the months to come.

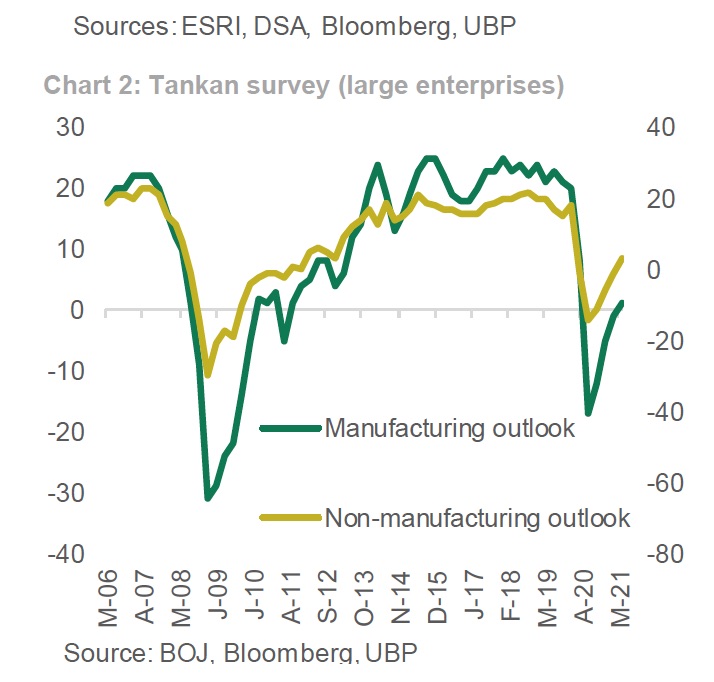

The latest Tankan survey, which is a quarterly poll of business confidence reported by the Bank of Japan (BOJ), also points in this direction. Both manufacturing and non-manufacturing conditions improved significantly to June (Chart 2).

We therefore project that growth will gradually pick-up in 2021, led by domestic demand (55 per cent of GDP), reaching 2.5 per cent this year. That would mark the fastest pace of expansion since 2010, but it still lags relative to other developed markets such as the US and the eurozone, where we expect GDP growth will reach 6.8 per cent and 4.7 per cent respectively. In 2022, we expect growth to remain relatively high at 2.2 per cent compared with 4.2 per cent in the US and 4.5 per cent in the eurozone.

No end in sight to Japan’s liquidity trap

While most major central banks around the world start to entertain the notion of policy normalisation, BOJ kept its yield curve control target for short-term interest rates unchanged at -0.1 per cent and 10Y Japanese Government Bond (JGB) yields at 0 per cent during its latest policy meeting on 16 July.

The BOJ also predictably revised down its sanguine growth projections for FY21 to 3.8 per cent from 4 per cent, citing consumption concerns. Similarly, the Cabinet Office’s latest economic report stated that weak consumer spending and a struggling service sector would probably hold back the recovery. The report highlighted the divide between Japan’s exporters, which have benefited from the global recovery, and domestic consumption, which may still take longer to rebound.

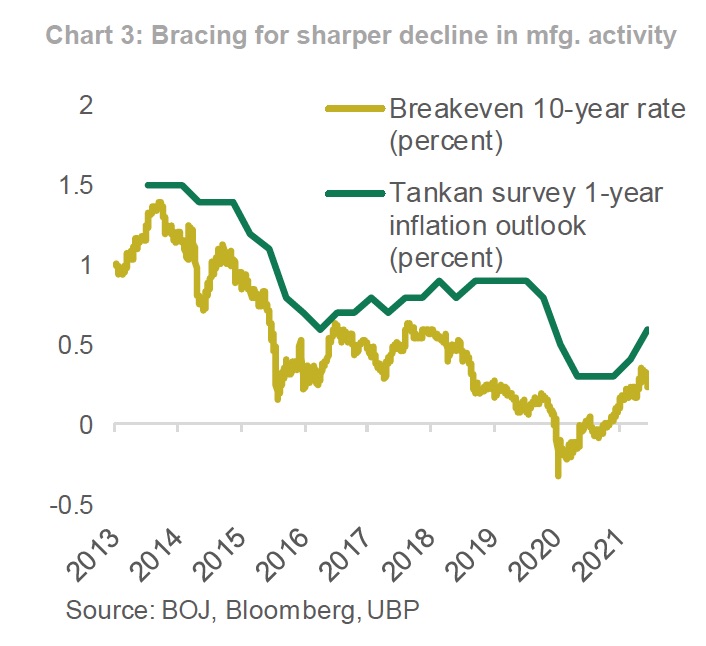

Lastly, the BOJ also noted a modest, albeit transitory, impact on inflation, stemming from higher commodity prices. Consequently, it also revised its CPI forecast up to 0.6 per cent for the year from 0.1 per cent. Despite inflation expectations improving in June (Chart 3), they remained subdued at 0.2 per cent year on and will remain significantly below BOJ’s elusive 2 per cent target for the foreseeable future.

This is because Japan’s economy is stuck in a long-term paradigm. Abenomics was Japan’s bid to upend the “Liquidity Trap,” a situation whereby conventional monetary policy is unable to shock the economy out of secular stagnation and deflation.

The most well-known analysis of Japan’s liquidity trap can be attributed to economist Paul Krugman, who argued as early as 1998, that the only way for BOJ to stoke inflation expectations was to “credibly promise to be irresponsible,” thereby officiating the debate on large-scale central bank asset purchases.

However, despite a massive expansion in BOJ’s balance sheet from 20 per cent of GDP in 2008 to more than 130 per cent of GDP in 2021 – a very credible shift in monetary policy regime – there seems to be no end in sight to Japan’s liquidity trap.

There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the government’s fiscal policy stimulus has been too subdued. According to IMF figures, Japan’s coronavirus response package amounted to approximately 50 per cent of GDP, or twice as much as the US at 26 per cent. However, the actual size of discretionary fiscal spending (or mamizu) is much smaller, around 16 per cent of GDP. This is in line with Japan’s enduring concerns about a potential increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, which is elevated around 235 per cent.

Indeed, Japan’s fiscal policy stance has remained restrictive over the years, with government consumption rising by around 3 per cent year-on-year on average between 1990 and 2020 and the budget deficit remaining broadly unchanged at around -4 per cent of GDP in 1980 compared with -2.9 per cent in 2019.

Moreover, structural reforms have been slow to implement. Women’s labour force participation rate (65 per cent) remains constrained by childcare shortages and a culture of long working hours, while the gender wage gap is the third largest in the OECD (27 per cent). Non-regular employment also rose sharply from 20 per cent in 1994 to 38 per cent in 2016 and most of these workers are women.

The crux of the matter is that for Japan to break free from its liquidity trap, it needs to fundamentally change its economic structure. Until that happens, expect very little change from the BOJ, with the onus in future falling on fiscal policy.

Implications for investors

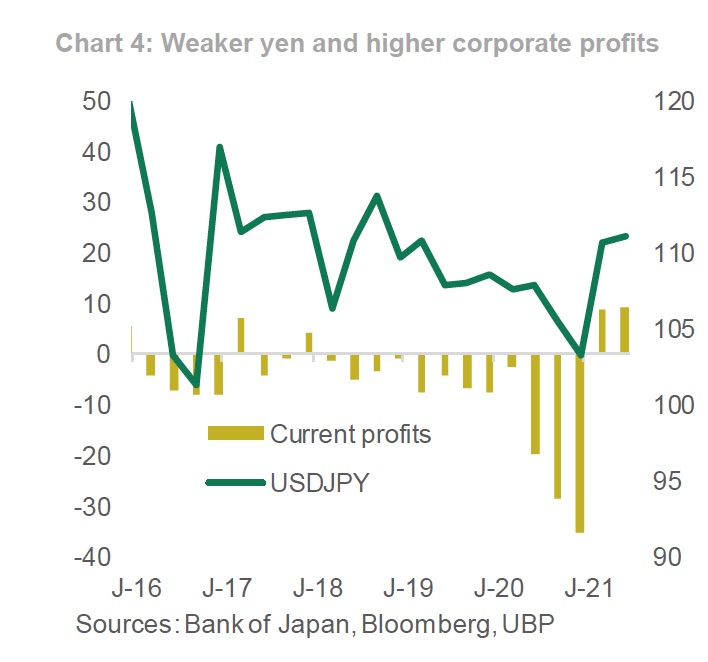

We expect that exports will lead the recovery in current profits in Q2-21 (Chart 4). Approximately 33 per cent of all revenues under TOPIX are derived outside Japan.

Japanese manufacturers are therefore beneficiaries of strong US demand and JPY depreciation, which should be supportive of better performance in Q2-21 and into Q3-21. The JPY has appreciated towards its 200-day level of USDJPY 106 recently. However, it is down -6 per cent year to date and we expect that the cross will remain above its 200-day level in the remainder of 2021, on the back of a stronger dollar.

Some risks worth highlighting

The TOPIX is trading at 20x earnings, above its long-term average of 18x and at a slight premium over the Nikkei. Also, although we do not expect the JPY to appreciate significantly in the remainder of the year, it remains attractive in REER terms, so we can’t exclude the possibility outright. In addition, the underlying increase in commodity prices will probably worsen Japan's terms of trade in the short term, further dragging on revenues.

In the medium-term, the balance will tilt in favour of companies in sectors that are more domestic oriented or have higher exposure to services. Areas linked to structural reforms should also yield returns, but this may still require some time to materialise.