Investment Strategies

Why Japanese Active Managers Will Keep Beating US Peers

Japanese equities provide a happier hunting ground for investment "diamonds in the rough" than is the case with the comparable US market, the author of this article claims.

There is more opportunity for Japanese fund managers to find market-beating returns – that all-important “Alpha” – than is the case in the US, so the author of this article argues.

The writer is Katsunori Ogawa, chief portfolio manager of SuMi TRUST’s Sakigake High Alpha fund. The editors are pleased to share these views and invite responses. The usual editorial disclaimers apply. To contribute, email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com

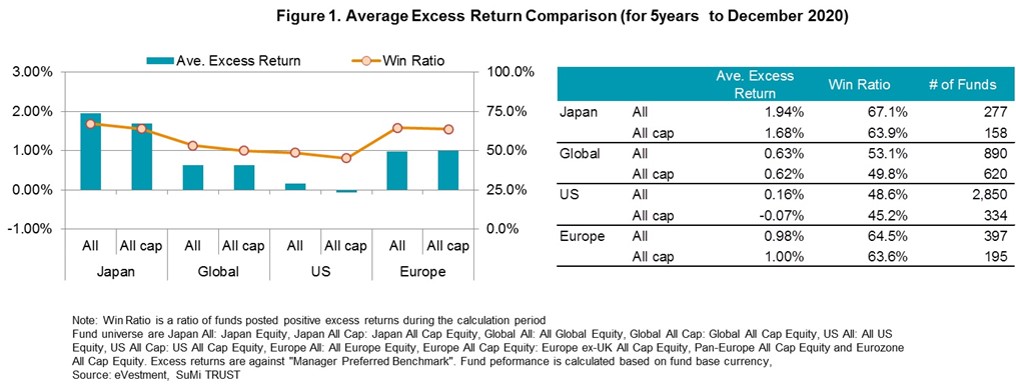

Japan is the world’s second largest stock market after the US but it is number one when it comes to providing fertile terrain for active equity management (see figure 1). Over the five-year period up to December 2020, the average excess return of active Japanese All Cap funds was 1.68 per cent while the equivalent for the US was -0.07 per cent*. To a lesser but still pronounced extent, the same holds true when you compare Japan with Europe.

The main reason for this big structural dissimilarity between developed markets lies in the fact that Japan has more - relative to the size of its economy - listed companies whose growth trajectories are easier to predict than the US, making active management much more effective. A secondary reason can be attributed to the significant language barriers as most Japanese companies still don’t produce documents in English and last, but by no means least, the fact that there are far fewer analysts covering Japanese stocks than their US counterparts.

We sometimes describe the impact of these differences in corporate culture and capital markets as the “autonomous regenerative function” of a market. Simply put the ‘autonomous regenerative function’ is the process in markets which causes weaker companies to be naturally weeded out. This decreases alpha opportunities for active managers and makes passive investing more worthwhile. Japan’s autonomous regenerative function is weaker than that of the US and this creates more alpha opportunities in comparison.

So why does Japan have a weaker regenerative function than the US? Totally different attitudes to M&A are a big part of the explanation. Many US companies actively engage in M&A and grow while proactively changing their business segments. For example Amazon, in the 25 years since its founding in 1994, has acquired more than 80 other companies and continues to grow. In addition, US companies do not hesitate to separate from business segments with less growth potential and reinvent themselves, such as General Electric which separated from and sold its original electric lightning business.

This means that US companies tend to behave like active fund experts and they are drastically and continuously changing in response to market conditions. As a result, it is harder for investors with research capabilities to predict the future stock prices of these companies. Consequently alpha opportunities for active funds become few and far between.

In contrast, in Japan there are few companies that actively reorganise their business through American-style aggressive M&A. Japanese companies aim for organic growth in their chosen business field and favour looser business alliances with partners (the prevalence of cross shareholdings is an example of this), rather than M&A activity. It is therefore easier for investors with research capabilities to predict the future of a company and this results in more alpha opportunities.

A second explanation for the difference in the strength of autonomous regenerative function between Japan and the US lies in the structure of the two nations’ capital markets. The US private equity and venture capital markets are mature and it is easier for even unlisted companies to raise funds, and there is little merit listing just for the purpose of raising funds.

On the other hand, in the Japanese market there are often few alternatives to listing for start-ups trying to raise funds. Japan’s private equity and venture capital markets are not as well established as those in the US, and listing standards are looser by comparison. As a result, there are a large number of companies on Japan’s main market, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) First Section, which have been unable to grow since entering the market. In a more regenerative market many of these companies would delist. However, with so few investors with enough private equity to increase the regenerative function of the market and with comparatively less strict delisting standards, many Japanese companies remain listed.

This creates opportunities for active management in Japan as there are far more stocks in the index with poor growth prospects, relative to the size of the economy. Indeed, since 1995 the number of listed US stocks has fallen dramatically while the number of listed Japanese stocks has slowly ticked up. In the US the number of listed stocks has been on a downward trend from over 7,000 in 1995 to 4,400 in 2018, while in Japan stocks are on a slight upward trend from 2,900 in 1995 to 3,600 in 2018.

The language barrier also creates a significant hurdle for foreign investors in the Japanese market as it makes conducting research, particularly on companies focused on the domestic market, much more difficult. If you look at some Japanese company’s websites you are likely to see information only in Japanese and if there is some information in English it won’t match the level of detail given in Japanese.

Overall, the autonomous regenerative function in the Japanese market works less well than in the US, with fewer companies merging with other companies and reforming themselves, and more companies with less capability to increase their own corporate value remaining in the market. Consequently, it is easier for stock pickers to forecast company growth because growth is more organic and stable and there are also proportionately more listed companies in the index with weak prospects an active manager can avoid.

This means that, even if fees for active management are higher than those for passive products, in Japan you can expect to receive corresponding returns. Despite some recent changes to the Japanese listing regulations and a reorganisation of the Tokyo Stock Market on the horizon, these structural differences between the US and Japan are not going to change radically any time soon – if anything the situation is growing more pronounced. Japan is therefore a market where it really pays to invest in active management.

About the author:

Katsunori Ogawa has been the chief portfolio manager of SuMi

TRUST’s Sakigake Strategy since 2003 and Sakigake High Alpha -

Japan Thematic Growth Fund, since 2018. He applies a thematic

top-down approach in addition to a bottom-up stock picking

approach to generate alpha for his investment strategies. He

joined SuMi TRUST in 1994 and was appointed client service

representative for public pension funds in 1997. In 2002,

Katsunori became a fund manager of Japanese equities and was

appointed to lead the Sakigake Strategy a year later. Katsunori

received a BA in economics from Keio University. He is a

Chartered Member of the Securities Analysts Association of Japan

(CMA) and a Certified International Investment Analyst

(CIIA).

*Source: eVestment