Strategy

Southeast Asia Business Partnerships â Three Steps for Success

Joint ventures and other models of partnership are a common feature of the Asia-Pacific private banking and wealth management industry. What approaches work for specific circumstances, and what approach should firms adopt? This article explores the territory.

The following article looks at strategies for success in Asiaâs wealth management industry, and how international as well domestic players can drive profitable growth. The article is from Singapore-based Justin Tan (more information about him below), who heads L E K Consultingâs Asia financial services practice.

These insights, drawing as they do on extensive data, are

important contributions to business development strategy; the

editors are pleased to share these views and hope they encourage

conversations. The usual editorial disclaimers apply to views of

guest writers. To comment, email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com and

amanda.cheesley@clearviewpublishing.com

Against the global backdrop of geopolitical uncertainties and other macro challenges, the exponential growth of AI and increasingly pressing inter-generational wealth transfer, Asia-Pacific has become the fastest growing region for wealth creation. This is not limited to China and Japan, or the leading offshore hubs of Hong Kong and Singapore, but includes the key onshore markets of Southeast Asia (SEA). These ânewerâ destinations offer wealth managers an unprecedented chance to tap into some of the most lucrative markets, characterised by a mix of entrepreneurs and business owners who have made their fortunes. These ânewly-mintedâ tech millionaires, and a rapidly-growing affluent and well-educated middle class, are eager to explore new investment horizons.

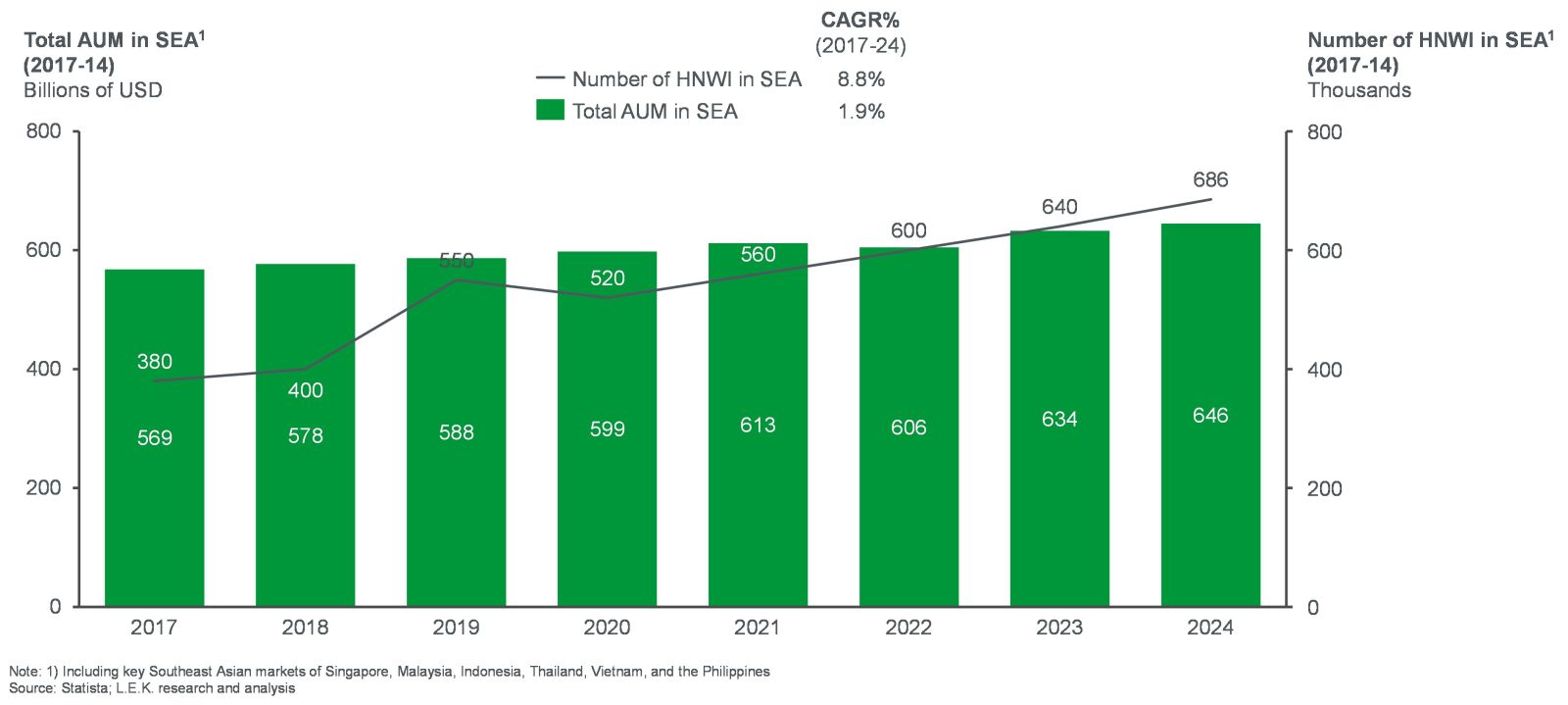

Exhibit 1 below shows that whilst total assets under management (AuM) have grown modestly at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) approaching 2 per cent during 2017 to 2024 for certain Southeast Asian markets, the growth of high net worth individuals has significantly outpaced the broader market, exhibiting a CAGR of close to 9 per cent during the same period.

Exhibit 1: Growth of total AuM and HNWIs in key SEA markets

Global private banks and wealth managers have invested significantly in teams covering key SEA markets, typically from offshore hubs such as Singapore, and leading domestic financial institutions, especially dominant local banks, have announced ambitious plans to capture their slice of the local HNW pie. However, whilst local banks may have broad-based client relationships across the individual and corporate segments, generally they still lack the capabilities, expertise and brand pull for competing effectively against well-established global private banks.

The global players also face significant issues, despite their substantial share of the burgeoning wealth. Their coverage model remains largely via Singapore, and their ability to penetrate the lucrative onshore wealth markets has been handicapped by a lack of an onshore presence, limited access to feasible local platforms to book assets, and modest brand awareness beyond the U/HNW segment with offshore needs.

To solve the problem, global private banks and domestic SEA banking groups have developed partnership models over the past five to10 years. However, although official figures are not publicly available for the partnerships, the jury is out on their success.

They are hard to get right but based on our own experience of negotiating and executing successful partnerships, below are three golden rules for achieving success.

Rule 1: No âone-size-fits-allâ model

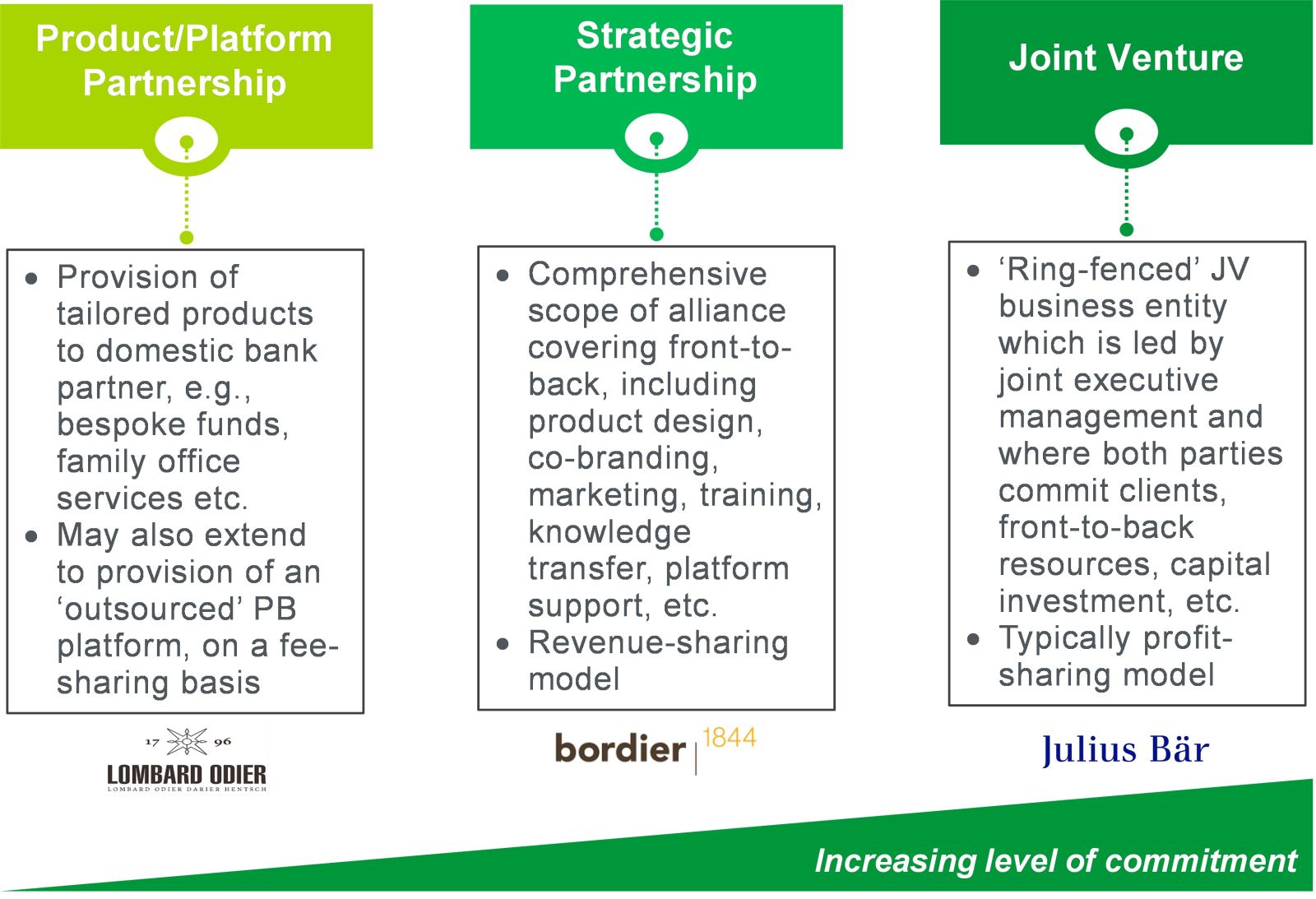

As illustrated in Exhibit 2 below, we have summarised the

plethora of partnership models observed in practice into three

major types, ranging from those more narrowly focused on product

and/or platform provision, to more comprehensive strategic

alliances, and finally formal joint ventures.

Market examples include Lombard Odierâs âproduct-centricâ partnerships with local banks in various markets, such as KBank in Thailand and UnionBank of the Philippines, Bordierâs pioneering private banking strategic collaboration with Military Bank in Vietnam, and Julius Baerâs onshore private banking joint venture with Siam Commercial Bank in Thailand.

Exhibit 2: Spectrum of private banking partnership

models

The logical follow-on questions are: how have these various partnership models performed, and has any one proven to be the âwinning modelâ? Our experience suggests that a healthy growth in AuM or revenue in the order of 30 to 50 per cent per annum has been achieved by more successful partnerships especially during the initial period, whilst others have faced daunting challenges from the get-go ranging from execution difficulties to compliance issues, leading to disappointing results. No single partnership model has proven to be the silver bullet; both parties need to agree on a partnership which aligns with their joint ambition, capabilities, and the realities of market execution. Naturally, the âbest fitâ partnership model is also closely related to the type of foreign partner selected by the local bank, with large, global private banks versus pure play boutiques offering significantly different value propositions â and expectations as well.

Rule 2: Success is not a zero-sum game

It is imperative to not only recognise that both parties can

benefit economically and strategically from entering a

partnership, but also to actively design a business and incentive

framework that explicitly encourages a win-win outcome. There

needs to be reasonable room for compromise in negotiating key

topics such as economic-sharing and management control. In one

situation that we have first-hand knowledge of, the local partner

had reservations about its previously negotiated 50-50 position

given its extensive local client network.

This had been a major stumbling block to realising the full potential of client referrals, until the control structure was eventually re-aligned. Importantly, such a win-win outcome should extend throughout the organisation and not remain at the institutional level. This is especially important when the new model directly impacts the client base, incentive structure and the modus operandi of core groups such as relationship managers, and investment and product specialists. These client-facing staff should view the partnership as an opportunity to elevate their proposition to clients, with the potential to share in a bigger pie, rather than be seen as a possible threat.

We have seen a partnership model focusing on referrals of wealthy business owners from a corporate bank struggling to get started due to a perceived misalignment of incentives. After a transparent review and tweaking the incentive scheme, the volume of referrals doubled over the next year and nearly 50 per cent of them converted to clients.

Rule 3: Marriage is just the beginning

The adage holds true here. Irrespective of the best efforts

invested by both parties in designing a sound business model and

robust partnership agreement, successful execution is a long

journey fraught with practical challenges, compounded by a

constantly evolving market and competitive landscape.

Like a marriage, there will almost certainly be unexpected issues that appear after the initial âhoneymoonâ period when both parties are brimming with enthusiasm and client, and asset growth tend to meet or exceed expectations. Both parties need to jointly navigate and overcome these hurdles and fully expect that building what is essentially a new business will be a long road.

Partnership agreements tend to be at least five yearsâ duration, and joint venture agreements are typically for 10 years, with built-in review milestones. Including an exit mechanism, subject to mutually agreed conditions, is arguably the critical golden nugget in any successful partnership agreement. It is prudent for both parties to invest the effort upfront to design a robust âpre-nuptialâ agreement, especially in the case of joint venture-type structures whereby clients may be pooled into the JV entity.

The last thing either party would want upon the dissolution of the joint venture agreement is to engage in a bitter dispute over client ownership and transfer arrangements, which risks causing irreparable damage to client relationships and institutional reputation. Ultimately, unlike a marriage, most partnerships agreements are not intended to last indefinitely, and an amicable separation should be the desired conclusion.

About the author

Justin Tan (pictured below) heads L E K Consultingâs Asia financial services practice and is based in Singapore.

Justin Tan

Tan is an experienced strategy advisor in wealth and asset management, as well as in banking, spanning retail, business, corporate and institutional. Financial conglomerates and private equity firms also turn to Tan for his assistance. He advises clients on strategy development, business growth and transformation, including joint ventures and M&A, organisational design and performance management, risk management and sustainability. Tan also helps organisations to develop robust AI-driven data analytics capabilities organically and via partnerships. Earlier in his career, Tan was head of strategy and business development for Merrill Lynch Wealth Management in the Pacific Rim.