Uncategorised

China's Course To Carbon Neutrality – Comment

China and the US have more in common than being the two largest economies. They are also the world's leading carbon polluters. Robeco's China investment specialist looks at the possible trajectory China is on to meet its net-zero pledge just as the two countries have held their first climate meeting this weekend.

The path to net zero is becoming as well worn a phrase in investment circles as ESG. As the world's biggest global carbon emitter by some measure, China's pledge to become carbon neutral within 30 years is a big ask but not beyond reach given how the country has transformed itself already over the past 20 years. From an investment and sector viewpoint, head of China Investments at Robeco Jie Lu charts what this ambitious path might entail.

It comes as the weekend saw a rare meeting between the two countries, when US climate envoy John Kerry met with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua in Shanghai; both vowed to take “concrete actions" this decade to reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. We welcome this timely contribution, where the usual editorial disclaimers apply. Email feedback to tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com.

China’s pledge to become carbon neutral by 2060 has left many observers both excited and perplexed. Making the world’s largest CO2 emitter carbon neutral within the next 40 years is no mean feat, and will have far-reaching consequences. But the formidable challenges associated with the transition also come with many investment opportunities.

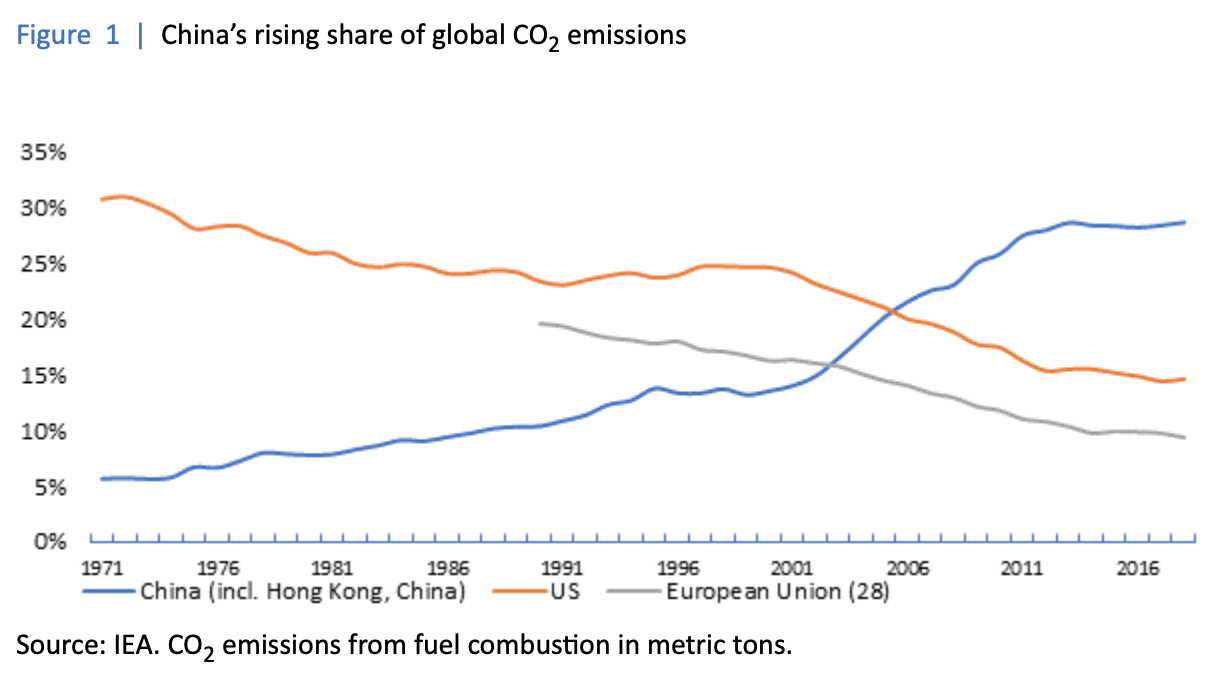

China is by far the largest carbon emitter in the world. The country currently accounts for close to 30 per cent of global CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), versus 15 per cent for the US and 9 per cent for the European Union (see Figure 1). Colossal investments will be required to help the transition, especially in areas such as renewables, the electrification of transport and nuclear power generation.

CO2 emissions may not be comforting, but tunes are

changing

The rapid pace at which CO2 emissions returned to their upward

path last year, in spite of all the havoc caused by the COVID-19

pandemic, is a testament to the disruption needed only to put our

economies on the necessary trajectory. So, while current trends

in CO2 emissions may not be comforting, the recent change of tune

at the highest level clearly warrants close attention.

Net zero carbon emissions will require combined efforts in three

directions. Firstly, a shift in the country’s gross domestic

product (GDP) mix, away from carbon-intensive industries such as

manufacturing and construction, towards more carbon-light

activities such as services. In fact, China’s gradual move away

from industrial activities started over a decade ago.

Secondly, a change in the country’s energy mix, away from coal

and oil towards renewables. Despite sizeable investments in areas

such as hydro, wind and solar power over the past decade, China’s

economy remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels. In particular,

China is extremely reliant on coal, which is arguably the most

problematic energy source in terms of carbon emissions.

Finally, carbon compensation plans will also play a key role.

Even with the most radical measures, full decarbonisation is

unlikely to be achieved without compensation initiatives. From

this perspective, carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS)

techniques, as well as forestation and reforestation, are likely

to become an indispensable part of the government’s toolbox.

Implications by sector

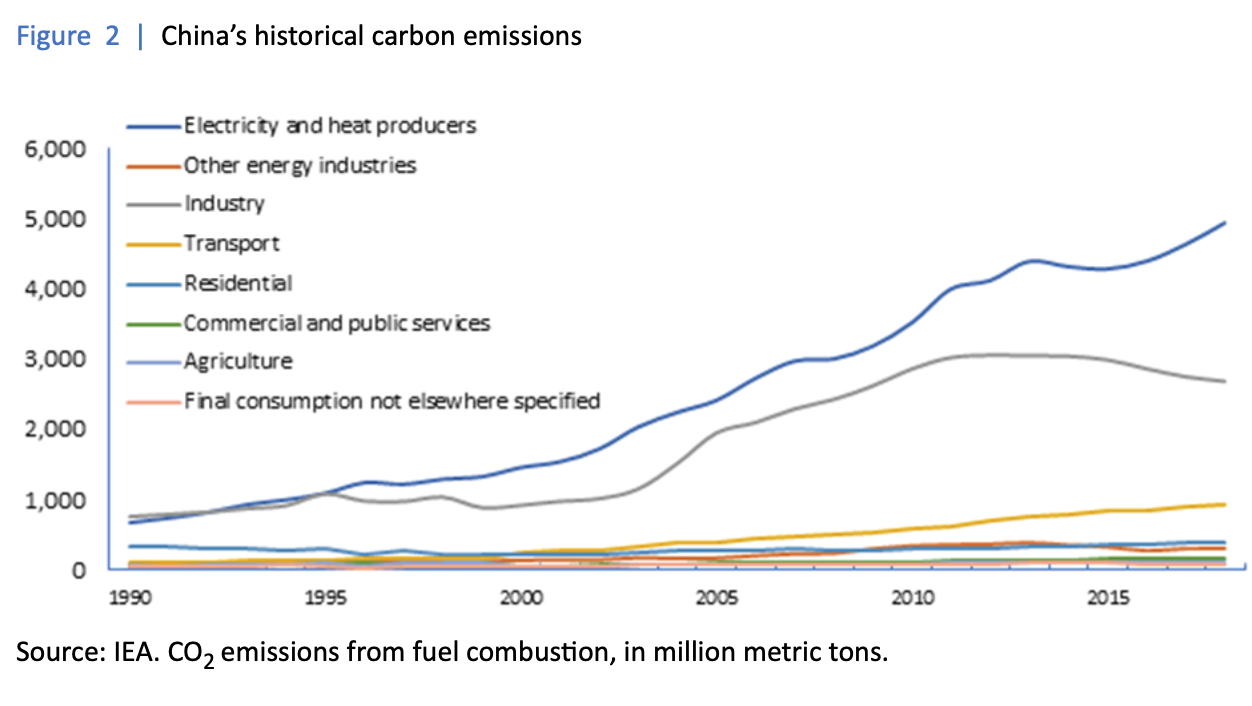

Around 90 per cent of China’s CO2 emissions come from electricity and heat production, industry, and transport, with electricity and heat production representing half of all emissions. Logically, these three areas will be affected most by the transition, with electricity and heat production at the forefront.

Yet there are also important differences across sectors. For instance, while industry emissions already peaked almost a decade ago, emissions from electricity and heat production, as well as from transport sectors, have yet to. But there are signs that the tide is slowly turning. For one, investments in coal-fired power generation have been slowing sharply over the past few years.

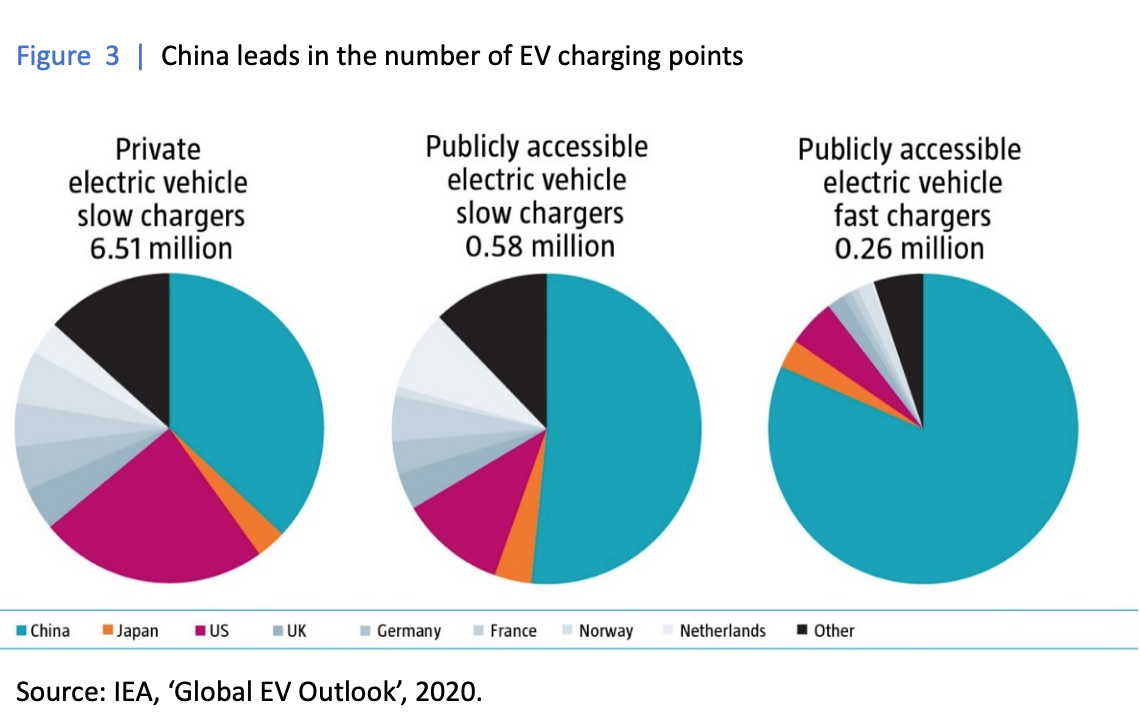

Meanwhile, moving towards a more sustainable transport sector will also require drastic changes, as well as sizeable investments. These include a greater use of public transport infrastructures, an accelerated increase in the use of electric vehicles, and a further improvement in the efficiency of conventional oil-powered vehicles.

Seizing investment opportunities

Given the changes needed in most sectors to achieve carbon

neutrality, the key issue for investors is to identify any major

risks they might be exposed to, and to find the most attractive

opportunities. Arguably, the most exposed companies are fossil

fuel producers, particularly oil majors. Their core business is

fundamentally at odds with decarbonisation.

Companies able to support transition poised to

benefit

But many other industries also stand to suffer from a

badly-handled transition, including petrochemicals, steel and

cement. Conversely, companies able to support the transition are

poised to benefit from the decarbonisation trend. In some cases,

the probable impact of decarbonisation is already well known but,

in others, the consequences remain difficult to fully grasp.

For now, we see opportunities in three major areas. Renewables are expected to retain the lion’s share of investments. But electric vehicles are also expected to be among the big winners. Finally, upgrades in power networks and energy storage technologies, as well as the hydrogen industry are likely to capture a significant portion of total investments too.

Recent official announcements suggest that there will be an

ambitious ramping up of clean power over the coming decade, with

the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy now expected to

reach 25 per cent by 2030, compared with an earlier target of 20

per cent. Given the gradual exhaustion of hydropower potential

and the slowing nuclear power additions, this target implies a

rapid step-up of wind and solar.

Beijing has also made it clear that it wants to continue leading

the way in new energy vehicles (NEVs), with a recently approved

plan for the industry. According to the plan, NEV sales are

expected to reach 20 per cent of overall new car sales by 2025,

up from 5.4 per cent last year. This target for 2025 is lower

than the previously stated target of 25 per cent, as it takes

into account the rough patch of 2019 and 2020.

Finally, while renewables will play the most critical role in the transition towards carbon neutrality, additional storage technologies will also be needed to address intraday and seasonal variability issues inherent to wind and solar energy, and to decarbonise all parts of the economy – including the most carbon intensive ones, such as steel and cement production.

From this perspective, two complementary technologies – batteries and hydrogen – are likely to play a key role, given their ability to convert electricity into chemical energy and vice versa. China is already the world leader in terms of battery manufacturing, accounting for around 70 per cent of global capacity. Despite the air pocket experienced early in 2020, production recovered quickly.

Meanwhile, developments in hydrogen are also set to accelerate over the coming decades. The China Hydrogen Alliance, a trade group representing the sector at large, estimates that hydrogen could account for up to 10 per cent of China's total energy mix in 2050, compared with less than 1 per cent today.